In the face of globalisation, growth in emerging markets, and increasingly multi-ethnic workplaces, the top-down management approach of decades past no longer serves all organisational environments. Instead, many companies find themselves needing to develop high-performance teams, under the guidance of inclusive leaders who focus on both personal and professional success.

“Inclusive leadership starts with an intention of wanting the best for the world, not necessarily the best in the world. It is a form of leadership that looks deeply into the role of the leader as a custodian of values, character and resources,” says Kurt April, Professor of Leadership, Diversity and Inclusion at the UCT Graduate School of Business and Associate Fellow of Said Business School (University of Oxford).

April, whose research over 15 years spans a wide range of leadership issues, says that inclusive leadership seeks to encourage the input of key stakeholders, valuing their opinions and welcoming the diversity of perspectives and experiences they contribute. A far cry from the pervasive hierarchical styles of leadership of old.

However, April says, “Even when this type of comprehensive change in management strategy is employed, the success of change is influenced by the resilience of individuals to cope with the stress of being at the receiving end of the change, and being comfortable in the uncertainty that naturally accompanies any change.”

For this reason, he says, enhancing the resilience of staff at work should be a key strategy of the inclusive leader.

Redefining workplace values can cause disruption, upset the status quo, and be seen as uncomfortable and threatening. It requires a shift in staff’s personal identity, requiring that they are open and adaptable in the face of change, and being willing to continuously unlearn and relearn. “When such fundamental individual changes occur, one needs ‘pillars’ on which to hold,” he says.

In the corporate environment, that pillar should come from top business brass. “The leadership should be visible in driving and supporting change to build common belief and commitment, and ensure that everyone is on ‘the same page’, even if everyone initially does not agree with the bold vision,” says April.

Becoming this role model begins with abandoning the hard power perspective, often characteristic of corporate leaders. Described as coercive, controlling and dominating, these leaders use their power and position to drive their own growth and selfish ends, rather than universal success. “It is a human trait to put ourselves at the centre of the world and attract willing followership by eliminating our concern for the smaller self, the selfish self, the material self,” says April. He argues that modern leaders should use soft power, in which they get others to strive for the same things that the leaders are, responsibly.

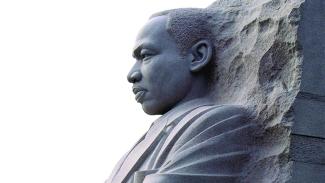

“This power is characterised by generosity, attraction and influence, the appeal of cultural, social and moral messages, a respect for others’ traditions, and an approach of deep care,” he says, noting Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr as examples of leaders who used soft power.

The four components of an inclusive leader

According to April, the modern leader must not only embrace soft power, but also embody four characteristic components of inclusivity. The first of these involves nurturing and building communities.

“This involves hearing the minority voice and widening the conversation. Helping others cope with uncertainty and avoiding the traps of absolutes, while teaching compassion and being comfortable within the grey areas of organisational life,” he explains.

In this way, actionable empathy is practised and an inclusive workplace environment is nurtured. It ensures that emotions, particularly defensiveness, do not get in the way of creative and flexible responses to change.

Secondly, inclusive leaders must be agents of healing. Faced with change, individuals can react with resistance, criticism and resort to old stereotypes. They can reject the new system altogether, even purposefully sabotage it, or become stuck in a workplace rut and psychologically withdraw.

“Leaders must help people work through resentment and become connected, restoring their sense of belonging and reconciling conflicting images of the past with a compelling vision for the future,” says April. Essentially, this means providing support by “actively taking stances against and opposing despair, and embodying hope in one’s words, actions and deeds,” he adds.

Hope closely relates to the third component of leaders as visionaries. By helping others see the potential and possibilities of change, they give a positive picture of why the chosen path is the way forward. “These leaders must move beyond just telling it ‘how it is’, and practise telling ‘how it could be’,” says April.

Finally, inclusive leaders must encourage staff to invest in personal renewal. Described by April as taking time out for serenity, selfreflection and gratitude for others, “it involves investing in those people and practices that make them mindful and resilient, living out a purpose and saying ‘no’ to all that is not in that purpose.”

Whether such self-care is experienced as chatting with friends or loved ones, taking spa breaks, going to the gym or simply enjoying a good meal, the time spent effectively charges people’s batteries so they can approach workplace challenges with renewed energy and vigour.

This component applies to leaders as well, particularly with respect to reaching out for help and guidance. According to April, “The more senior a person is in an organisation, the greater the apparent difficulty in admitting to a problem and asking for help.” Interestingly, his research shows that women leaders find it more difficult to ask for, or take help, than men – they therefore suffer greater burnout and depression when compared to male leaders.

Those in powerful positions may feel that admitting to a problem or asking for assistance is weakness. However, a good leader understands that their role is not only to boost the resilience of others, but to reinforce their own ability to thrive as well.

Modern workplace

The role of inclusive leadership in the modern workplace is gaining momentum. Indeed, data published by Ernst and Young in November 2013 revealed an overwhelming majority of business executives reported inclusive leadership, or the ability to encourage teams to voice diverse perspectives and dissent, is an effective means of improving performance.

Furthermore, those who rated their organisations as ‘excellent’ at building such teams were more likely to have achieved earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation growth of greater than 10% over the past year.

However, despite the obvious benefits of this business model, half of the organisations surveyed said they lacked leaders with the ability to manage and motivate such teams.

“In today’s business environment, leaders need to be inclusive in order to integrate diverse perspectives to create highperforming, global teams that drive growth for their organisations,” explains Mike Cullen, global talent leader at Ernst and Young.

“Organisations are realising that they must develop the relevant leadership skills in their people to help transform the diversity of their global organisations into a competitive advantage.”

That development requires organisations to turn against the hard power, top-down methods of the past. They must instead grow a new generation of soft power leaders who will support the personal and professional resilience organisations need for the modern, teamwork-driven workplace – while still achieving the necessary results.

“This requires continuous active stances against the evidence to change the deadly tides, which could lead to despair. It is not just about being optimistic or merely speaking about what could be, but actively getting involved and taking purposeful steps to help bring those possibilities to fruition,” says April.

By embodying the inclusive leadership components he outlines, modern business leaders can ensure this fundamental shift in practice is carried out smoothly. With the necessary humility they can help staff see that change in itself is not inherently bad, but can facilitate learning, renewed motivation, personal growth and development, adaptability, and hope.

In doing so, they establish the long-term, sustainable success of corporate goals. Says April, “inclusive leadership is the basic call for all of humankind to become more than we currently are. But you can only be more if through purposeful action, you help others and allow them to be more than you. You cannot be more if you don’t know how to be less.”