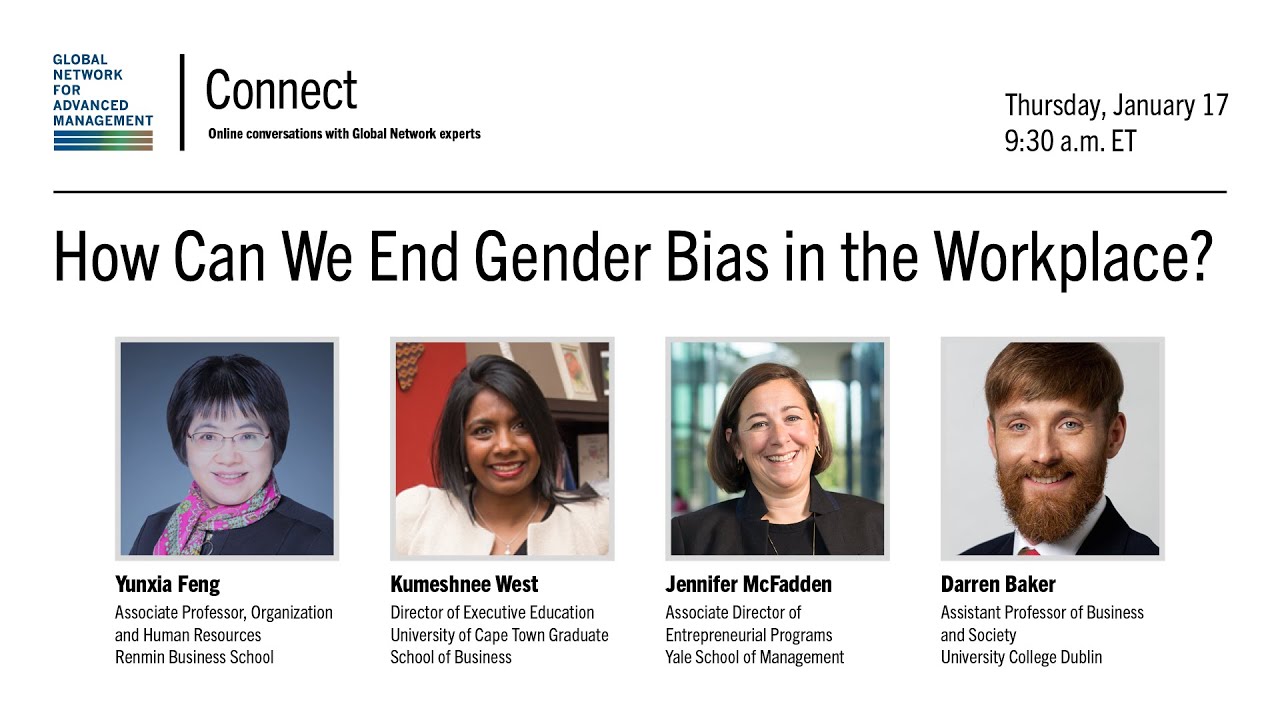

Women remain underrepresented in many industries, especially at the highest levels. The #MeToo movement illuminated the bias—and sometimes hostility and abuse—that women face in many organizations. And as a 2017 Global Network Survey showed, women face conflicting signals about their societal and professional roles. During the first Global Network Connect webinar event held on January 17, experts talked about the steps, large and small, that can contribute to gender equity in the workplace. Watch the webinar and read some of the highlights from the conversation below.

Kumeshnee West has noticed a pattern.

West meets with women at all levels of management in her role as director of executive education at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business, including corner-office executives and younger women looking to advance their roles inside a large organization. Often, the women are referred to the program by their supervisors for training in interpersonal skills.

“They come into some of our courses to learn skills to be able to communicate in a more powerful way, and yet when you sit with them and we have conversations, we see that their communication style is perfect,” West said during a Global Network Connect webinar held on January 17. “They all have the academic qualifications and are ready to step in and step up, but they often face challenges where their colleagues expect them not to succeed. That becomes an obstacle for them inside the organization.”

West discussed gender bias in the workplace at the online event with three Global Network colleagues: Darren Baker, associate professor at University College Dublin; Jennifer McFadden, associate director of entrepreneurial programs at the Yale School of Management; and Yunxia Feng, associate professor of organization and human resources at Renmin Business School.

The venture capital sector in the United States faces particularly large hurdles when it comes to gender equality, McFadden said. According to All Raise, an organization that tracks gender diversity in technology companies, only 9% of decision makers at U.S.-based venture capital firms are women, and nearly 74% of those firms do not have any women as investors at all.

That creates problems for female entrepreneurs looking to get their products and ideas funded. “You may have a great idea, you may get down the path, you may be acquiring users and doing all of the things that are correct, but your opportunity to get to those venture capitalists—ones whose networks are built on personal connections and largely dominated by men—is stymied immediately,” McFadden said.

It’s all too easy for startups to replicate those male-dominated networks. Firms that do not build diverse teams from the start find themselves in “diversity debt,” McFadden said. “If you are not baking in that diversity at the earliest stages of your company, it’s really difficult to unwind…if you have an engineering team that has, say, five white guys on it and you try to bring in a female, you’ve created an environment that is not terribly inclusive to that individual.”

Changing corporate culture means companies need to address long-standing myths that contribute to inequality. Baker noted that inequality can arise from an emphasis on “confidence” and “resilience” in the workplace—terms that have long been associated with masculinity. “When they’re used in specific organizational contexts, it can lead to disadvantages for women,” Baker said.

Baker’s research has shown that frequently, women are reluctant to talk about their own mistreatment in the workplace, and will sometimes blame themselves for the troubles they face. One step for organizations is to create confidential spaces for women to share their experiences, so that managers can learn what is really impeding women’s advancement. “There is this sense among women that they have to guard themselves, stand up, and in a way, show their equality,” Baker said. “If organizations can help women build their support networks, that might give them a greater voice in reshaping organizational systems.”

Another way to address inequality is acknowledge the work-life balance challenges that women face as they rise through the ranks, Baker said. “Organizations should be cultivating men as inclusive leaders. They should celebrate the achievements of women, as well as encourage them to demonstrate that they have responsibilities outside of work, perhaps in terms of picking up children from school or activities. When that happens and say, a woman needs to leave the workplace early, then it’s absolutely fine.”

McFadden agreed, adding that organizations should stay away from “maternal” or “paternal” leave to avoid defining gender roles, and instead use a more generic term to make taking time for family responsibilities acceptable for everyone in an organization.

“Human beings have lives outside of work,” McFadden said. “How can we set up a structure that makes everybody feel like they have those lives and then lead by example? It shouldn’t just be extended maternity leave. It is parental leave.”

In China, Fen said, a business culture largely dominated by men is beginning to shift, in part because of generational changes. “In the Chinese context, men who were born in the 1980s or later have a different attitude and better opinions when it comes to gender diversity,” Feng said.

In a younger couple, she said, spouses might both attend business school at the same time, as a way of showing that the family unit supports equality.

It’s an example of the way that China’s pragmatic approach is being applied to workplace norms. “Corporate culture in China is largely viewed as ‘what is functional?’ meaning, ‘what works best to fulfill the strategy we are looking to use?’ It’s a business-driven role that isn’t always viewed in the context of gender, but I think that is starting to change.”

Business schools can play a part in leveling the playing field, Feng said. She noted that more women at Renmin Business School are traveling for international exchanges, like the Global Network’s Global Network Weeks, and being exposed to different cultural norms. Then they bring those ideas back to the business culture in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. “We have these deliberate strategies to help women prepare themselves for the challenges that await them in the future.”